| Cycling Mexico |  | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Nothing compares to the simple pleasure of a bike ride. J.F.Kennedy | ||||||

| Three-month cycling trip, starting in late August 2010 in Tijuana, ending in Cancún. 7th expedition by the author. (Previous expeditions : New Zealand, Australia, USA, Canada, Alaska, Japan). |

|

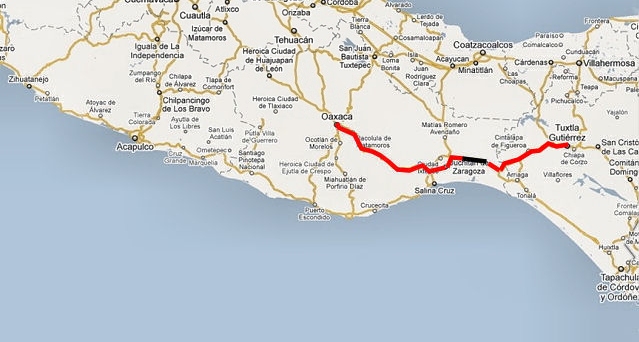

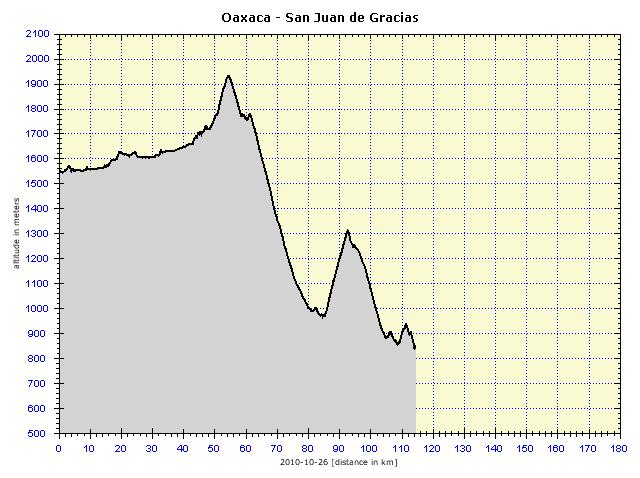

To Tuxtla Gutiérrez To the Pacific Along the way, there were also plenty of Mezcal distillers, although they proudly call themselves factories. Mezcal is alcohol “with a worm”. Like Tequila, it is distilled from Agave. I can not tell the difference between them. Here, however, Mezcal is presented as Oaxacan Gold. In the center of Oaxaca, tasting is offered and there are subsequent sales on almost every corner. Sales of Mezcal are combined with sales of the works of local folk artists (artesians). There were perhaps 30 such stores in Matatlán—a small village en route. Thereafter, cycling was in the mountains with little civilization, first uphill, then a wonderful downhill descent of 30 kilometers, with plenty of hairpin bends which required full concentration on the bike. Then again a significant climb, followed by a descent. In the heat, I gradually began to look around for the possibility of an overnight stay in the tent. Surprisingly, it looked bad. In the deserted mountains, the only flat areas were near the road, otherwise there were steep banks covered in cactuses and shrubs. The tiny village of San José de Gracias appeared (it was not on the map). It has a few restaurants to serve bus passengers, the drivers of which seem to have a mandatory break there. At the end of the street, there was a hotel. I checked into the accommodation as their sole guest, and went out to dine very well and cheaply at the roadside restaurant with the largest number of customers.

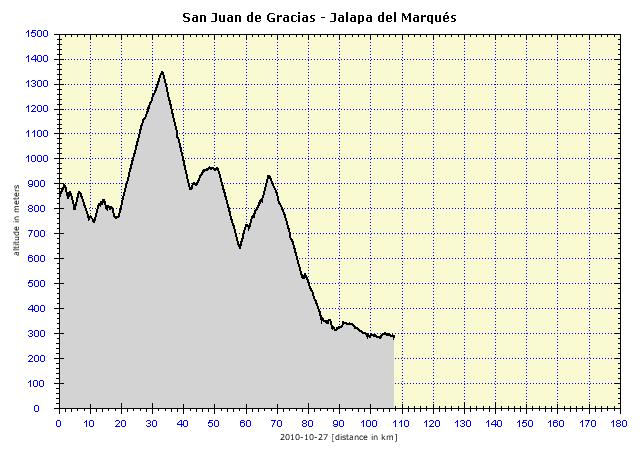

The next day was similar. A beautiful route through the mountains, very hilly. Although I kept losing altitude, I still had to climb quite a few hills. Along the route, there were a few poor villages and two towns – El Camarón, and Jalapa del Marqués near Lake Juaréz, where I stayed overnight. Near the road, I saw several Mezcal production plants, which provided for the first stage before distillation, and then also a few real distilleries. That evening, in Jalapa there was a ceremonial procession to the church, with youths solemnly and proudly bearing huge candles, women carrying flowers. All of which was naturally accompanied by clamorous music. This type of procession is not seen in our country. Again, I managed to eat well and cheaply. The town itself had no restaurant (not even the cheapest type – cocina económica), there were only women in the market selling tacos and other food. The restaurant was about 1 kilometer from the town center, near the bus stop on the main road.

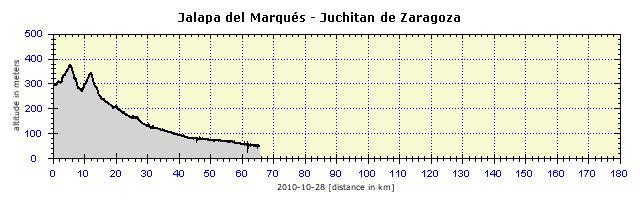

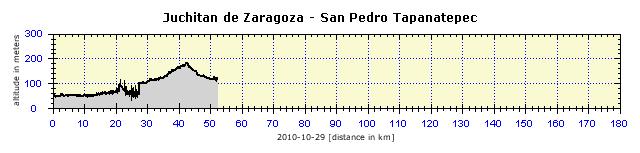

On paper, it looked as if I would be enjoying civilization the next day. First there was the small town of Santo Domingo Tehuantepec, which appeared to be nothing much at first glance. Then, a town of about 70,000 inhabitants, Juchitán de Zaragoza, was situated about 10 kilometers from the Pacific coast. Here the local famous wind already manifested itself. I faced it almost head-on, so the 30 kilometers were very laborious. At the entrance to the town there was a commotion. Several kilometers of cars, buses and trucks were lined up on the main road. It was some kind of political protest. The road had been closed by the people, notwithstanding anything else. No cops were dealing with it, everybody had to wait until the protesters were tired of protesting. On the bike, I could of course pass by all the waiting vehicles.

The town was ugly, unsightly, even the church in the center was not much to see. The whole center was occupied by one huge market. I bought vegetables and fruit (apples, avocados) from the women wearing traditional colorful clothes. There were lots of horse-drawn carriages, cargo bikes and mini taxis in the form of motorbikes from which bulky passengers were overflowing into the street. I was probably the only foreigner there, everybody looked at me, and I politely greeted them all, it always works. I found a seafood restaurant. It was full, although not actually cheap. I had mussels which were delicious. However, about two hours later I discovered that the mussels were apparently not compatible with my inland stomach. My stomach felt laden, but I had no diarrhea or vomiting. So I concluded that I would sleep it off, went to bed at 9 p.m. and slept for 10 hours until 7 a.m.

Destructive Wind Storm I was alone on the closed road, I was cycling on the center line and still the gale blew me into the ditch twice. The second time, I fell over the handlebars and broke the left mirror. The blasts were so strong that when I braked hard, I almost tipped over, and when I braked gently, the bike would not stay on the road. It was clear to me that, in normal traffic conditions, I would literally not have survived this. In addition, the blasts of air from passing trucks would have knocked me down, it would simply not have been possible. When I finally bumped on to the main road, I got off the bike and pushed it for several kilometers. Even this was difficult, the wind was trying to blow the bike and me from the verge into the ditch. I wanted to find a bus shelter in which to survive this critical period. An amigo in a small truck stopped next to me, saying it was really dangerous. We loaded the bike on to his truck and he drove me the 50 kilometers to Zanatepec. He even invited me for lunch. I refused, my stomach was not yet ready, and he gave me a CD of genuine Mexican music. Great guy! I was sorry about my bad Spanish. After I started cycling again and the gale had changed into a slight breeze behind me, the body remembered the stomach problems, so I had to go into the woods a couple of times. Despite my aversion to drugs, I at least took some charcoal, cycled to the nearest town and found accommodation there. In the evening, I cooked some nutritional spaghetti, drank no beer and hoped that, in this way, I would be fit again the following day.

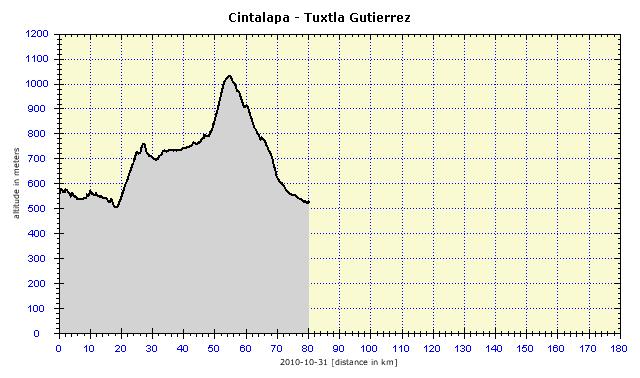

In the morning, it seemed that everything was all right. I had no stomach ache, but did not enjoy breakfast, as I had no appetite. So it was not completely OK yet. In the mornings I am usually as ravenous as a wolf and can not start the day without a proper breakfast. At least, I drank plenty of tea. The road was demanding and the first 35 kilometers were still pretty uphill. In addition, a very strong headwind was blowing against me in the saddle. Due to the lack of food, I did not have much strength, so I was a bit worried. Then I reached the plateau and there it was already just slightly breezy. Without the strong headwind, it would have been a great recreational ride. Still I was not hungry, but at least ate a banana and an apple. In Cintalapa, another unimpressive town (locals will forgive this comment), I suddenly got hungry, but not for just anything, just for a hearty soup. It took some effort, but I found a restaurant with exceptionally poor service (very unusual in Mexico), but great soup. I ate it without any further problems, so I thought the digestive crisis was over. I would try to down a test batch of red wine after the soup, this would confirm it.

Although my destination town was at the same altitude as the one I had set out from, even then I was not spared from cycling up- and downhill. The start was almost 20 kilometers on flat terrain, followed by a 35-kilometer climb and ending with a 25-kilometer long and wild descent. And while whizzing along at a speed of 55 kph downhill in pretty heavy traffic to Tuxtla Gutiérrez, a city of half a million inhabitants, I was thinking that if the bike failed and I fell off at that point, I would really be crushed to powder and they would have to scrape me off the road with a spatula. Well, the next day was the Day of the Dead, wasn't it? .

I had not realized how real the danger had been. When I removed the front bags in the hotel, I discovered that the left front pannier rack was missing the center bolt and therefore the brace rods were loose and at the appropriate time could have got into the front wheel spokes. I wondered how this was possible. Indeed, I am not an idiot and check the carrier screws daily, tightening them from time to time. It turned out that the bolt had broken and its end remained in the thread of the fork. It seemed that I would have to go to the outskirts to find a home mechanic to drill off the rest of the bolt and re-cut the thread. I did not worry, Mexicans are very skilled mechanics. This can be seen from the terrible vehicles which they manage to keep running. It was Sunday, but that was not an obstacle either, when they have work, they willingly toil at any time. The rest of the bolt was sticking out about one millimeter from the inside of the fork, so I managed to grab it with pliers and carefully unscrew it. Of course I carry spare screws with me, so I fixed it in a moment.

Oh Graveyard, Graveyard, Garden Brightly Colored

Then I realized that I also had my dead, and therefore I had something to commemorate. I sat down on a bench, watched some quarreling parrots and remembered my parents, grandparents, in-laws, friends. I went through the full list, remembering all the good things, until the darkness caught up with me on the graveyard bench and it was time to leave. The atmosphere made me really remember, recall faces and typical behavior and retrieve many memories. There is really something about the Mexican celebrations. Día de Muertos The sole, but prime, attraction en route from Oaxaca to Tuxtla is Canón del Sumidero on the Grijalva River. It can be viewed either from several observation points on the road, or by sailing through it by boat. The boat dock is in Chiapa del Corso, about 15 kilometers from Tuxtla. Originally I wanted to buy a half-day trip from Tuxtla, which was relatively expensive at 500 pesos. But then I came to my senses, I would not be carried like a trained monkey, I would manage it all by myself. A colectivo (minibus) travels to Chiapa del Corso every minute for 10 pesos and the two-and-a-half hour boat trip costs 150 pesos. Privately operated public transportation is great. There is no timetable, but colectivos run virtually all the time. It is impossible for a driver to depart in front of someone’s nose, as happens with Prague public transport, as he would be losing money. On the contrary, the driver always monitors the scene, honks at potential passengers and does not hesitate to stop anywhere or even to reverse 100 meters. The colectivos in cities have one fee (in Tuxtla, it was 4.50 pesos) payable in advance. The driver will stop at a wave, the route is written on the windshield, you can also get off anywhere along the route. In long-distance vehicles, the driver remembers where every passenger got in and charges them as they leave, according to the distance traveled. There are no season tickets, no discounts, but with such cheap fares, those make no sense. I would even prefer this type of service in Prague. Canón del Sumidero

The boat trip was an extraordinary experience. Some of the gorges are only several meters in width, the surrounding rocks dropping almost vertically from a height of 1,000 meters. We saw more than 30 crocodiles, the canyon is literally packed with birds and butterflies flitting around. There were several small waterfalls nourishing the lush greenery on the perpendicular rocks. There are some very interesting caves with not very impressive stalactites. One cave contains a small chapel with the requisite Virgin Mary of Guadalope. At the end of the canyon is a dam. Several thousand pelicans were in the lake in front of the dam. The captain “ecologically” scattered them by driving the boat fast towards them. The swarm of frightened birds flew around us for some time. The only negative was that part of the river was virtually covered in garbage, especially PET bottles. If I understood his Spanish comment correctly, the captain said that the garbage came from Guatemala. Regardless of the littered river, no visitor should miss the boat trip through the canyon.

Just like "High Noon"

|